A new horror story by the Fiction Fairy, Fey Cosmo.

TRIGGER WARNING: This contains confronting themes and is recommended for those aged 15 and up.

Dear Reader: The serial, “Brethren of Judas” is on a mental health/research hiatus, as the topic of coercion right now is a difficult one for me. Please enjoy ‘Flowers For the Lady’, a one-off story of cosy, modern horror.

NOW

When I was eight, in the old country, my grandmother died while my mother was carrying her from the bath to the bed.

She had been fighting cancer for seven years, after being told she had only months to live. The story, told so often I can recite it from memory, is that the doctor gave her the bad news and she gave him the finger and walked out calling over her shoulder, “I’ll see you in Hell”.

Maybe they met down there, or maybe in Heaven, but I know she’s back tonight.

THEN

Mum was fussing over our clothes obsessively, as she always does when we’ll see Tia Rica. That’s not her name, by the way, just what we call her amongst ourselves. She married a butcher, so she’s as rich as anyone in our family can possibly hope to be, in our part of the world. Her children, our cousins, always have fashionable new clothes while we dress like awkward little scarecrows sponsored by the Salvation Army, or Lifeline.

My family is a sad joke to them because we’ve only been in this new country for three years. They have what we crave, their own house with no landlord, a terrifying word, a house that no one can kick them out of. Two cars, like millionaires. A Nintendo with Super Mario on it, that they play on a TV in one of the boys’ rooms. We only have one television in the living room, and no console, and one car and our cousins lord it over us like pompous little kings of Mario Land. They don’t need the cheat codes for games, they have money, the ultimate power-up in life, and they never let us forget it.

Truthfully, their comments make me nervous, and being nervous activates my terribly weak bladder. I turn red easily, or I laugh or cough too hard, and suddenly I’m as wet as a sponge. I’m not too close to my period, in fact, I’m a little scared of it, but I already wear pads on special occasions to avoid the smell. But not every occasion is a pad occasion, because they are expensive, and today mum skips it. In the back of my mind, I know we’ll both regret it when the accident occurs, and the smell follows. But it won’t be the sighting of the ghost that causes it, ironically.

The ghost won’t even have a cool name, his name was John, and he wasn’t a friend, more of an ever-present nuisance in our class. He was naughty, loud, and never paid attention. He was a puller of braids and a thief who stole chip packets. Over the two-week holiday between term 1 and 2, he and some friends broke into the local high school to play handball. Someone, we don’t know who, threw a tennis ball too high and it landed on the roof of the school hall. John climbed easily onto the roof, easily fetched the ball, then easily stepped on a skylight. It couldn’t hold him, so he fell through and died.

We were shocked, I mean we were only eleven and in year 5, but we were familiar with death. Hayley, a sweet, shy girl from our class had found her father hanging in the closet one day and we heard all about it. Diva and Prisha had watched their grandfather collapse while gardening, and I… well… I had the Shadowman, but I hadn’t shared that one like the others had. But now 5H had something binding us together, from the quietest, weirdest nerd like me and my friends, all the way up to Candice and Stephen, the coolest kids that we all wanted to be. John’s death had glued us all together as he was still playing handball in our thoughts.

We snap back to the ugly reality of driving to see Tia and her unbearable children when dad pulls over in front of her house, reminding us to walk carefully through her garden. Her flowers and plants are fancier than anything we have because we cannot afford much. Mum and dad can barely afford to feed the giant, constantly hungry German-Shepherd cross breed dog who guards our house, but we keep her because she’s terrifying to the neighbours. They haven’t stolen anything from our yard since we got her, but it could just be a matter of time till they need money and then our lawnmower will disappear. Carefully my sister and I pick our way through the path in the dark, up to the fancy, large white house with the polished wooden floors. In defiance of everything we’ve been taught, Tia’s lawnmower sits brazenly in the open, not locked up or hidden away.

She kisses our cheeks with the same disdain as normal but fusses over her half-brother, my dad. Mum once drank just a splash too much at a BBQ and cattily sneered that Tia may have the fancy house, but she didn’t have everything, meaning my father. Sure, her fancy butcher-husband and our “Uncle” Ronald made them rich, but he wasn’t funny at functions like my quick-witted, charmer of a dad. Meanwhile, my brother was seated right next to my father while the whole family admired his good looks as my father’s clone. I didn’t know at the time, but the strange visitor I would later see was already there, observing. Maybe that’s why they spoke to me.

Tia always had good meat, so at least we ate well. Leaving the noisy dining room, I went to the peaceful living room and “home theatre”, where Ronald’s collections of videos lived. They also had tv you had to pay to watch, which was mind-blowing to me. I curled up next to my sleeping sister, who could fall asleep at the drop of a hat if she was full, even on the couch with me. I had my bookbag from school because once the adults started talking about the old country, the war and politics, there was nothing for me to do. My brother would get to play Nintendo with the cousins, easily accepted into the secret male cabal of gaming that we girls were banned from. I took out my horror story compilation and got comfortable.

I loved reading, and the library, and borrowed anything with a remotely creepy looking cover. Ever since I first woke up screaming about the Shadowman, my mind has been comforted by the idea that the dark is not empty, its just waiting to reveal itself. Even in this new country with a different history and heritage, there is still darkness. It had only been a few weeks since John had taken his tragic steps and his organs had been donated and that fascinated me. This story, the Tell-Tale Heart, seemed to be all about the beating noise from under the floor and the sickly white eye of the old man. I loved the idea that the heart was separate from the gift of life itself and that somewhere, a little piece of John lived in someone else.

“You have sauce on your cheek, mija. Here.”

Barely looking up from my book, I took the delicate white handkerchief and wiped around my mouth. I was a greedy little eater, even at an early age, maybe because we were never sure how much money we were going to have, and I had wolfed down the steak leaving tell-tale smears. Wipe, wipe, wipe, then back to the Tell-Tale Heart. I went to hand back the handkerchief and mumbled, “Thank you, Tia.”

“De nada, mija, you can keep that.”

Now I was FORCED to engage. Tearing my eyes away from my book, I looked over to Aunty, prepared with the adult-created script of, how are you, how is your arthritis, your house is so lovely, we love it when you invite us. But I couldn’t deliver my lines because I didn’t recognise the beautiful lady beside me. All I could do was stare.

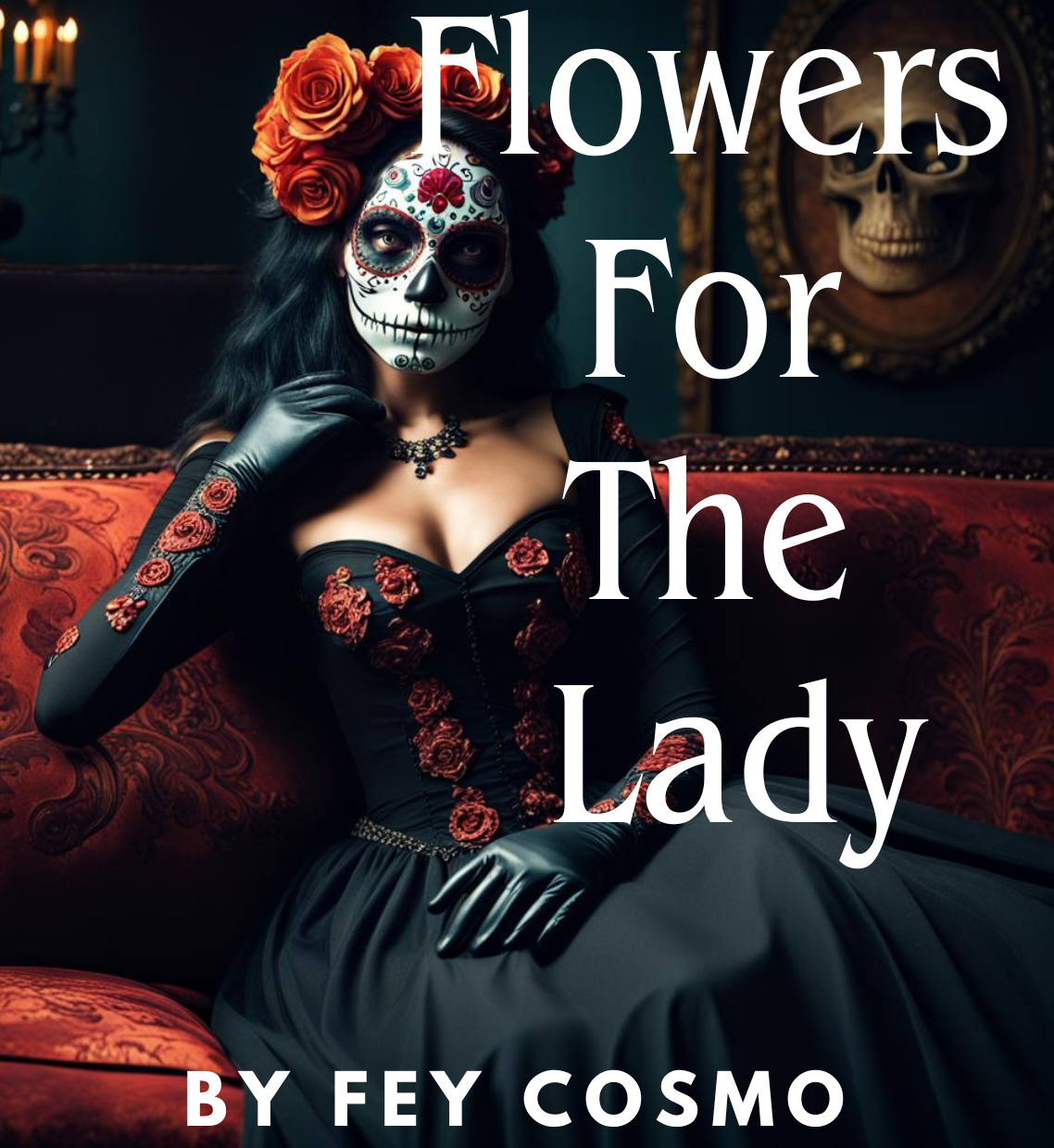

She was tall, taller than mum and Tia, maybe as tall as dad, and she smelled strongly of flowers, wax and soil that was just turned over. On her head was a crown of orange roses, and her long black hair tumbled free and thick. She wore a beautiful mask, like the ones I grew up seeing for Day of the Dead. It made perfect sense, after all, that’s why we were here. Technically, this party was not about meat at all, it was a celebration of all our dead. We’d readied ourselves without looking in the mirror because they were all covered, lest we see the dead standing behind us. Mum had lied for so long about loving her father more than anything, but I think she was scared to see his face behind her in the mirror, so she was very careful about covering them. Maybe she was worried she would see him. He’d be reaching for her hair to pull it from her scalp, telling her that lipstick was only for a puta.

This Lady, whoever she was, was not afraid of that word as we were. We’d been told that a puta was a woman who slept with men, which was wrong, because a woman is meant to be a mother and not a pretty display for men. But this Lady was beautiful and alluring, despite her strange clothes. She wore a black corset with roses on it over pale skin and a full black skirt. I could not see her smile, but it radiated out of the eyeholes of her colourful, painted skull mask. The fabric of the skirt near her feet seemed to tell a story. There was a boy with sandy hair, tennis balls, a man lying in a garden, a closet, a bathtub, a bottle, a baby blanket and two hands, smeared with something. All of those had to mean something, but I couldn’t piece together what. I wanted to ask her who she was, but something told me not to, so I just stared.

“Are you having a good fiesta?” she asked. Her voice was slightly muffled by the mask, but it was a real question. She pulled out a fan from the many folds of her skirt and delicately fluttered it around her, waiting for an answer. “Yes, its lovely,” I lied.

“You don’t need to lie to me, mija. What do you really think?” Again, I could hear the smile.

“It’s boring when the adults talk for hours, so I bring my books. But the food is good, and mum and dad are having fun talking, so its fine.”

“I like books too. Do you like the way I’m dressed?”

“Absolutely!” I gushed, a bit too enthusiastically. I had seen Beetlejuice and I loved the goth aesthetic without even knowing what the word aesthetic meant. “You look amazing! I love your skirt!”

“I like my skirt too. Your mother, she follows the old rules about the mirror, yes? And the offerings?”

“Of course. Our tata, grandfather, he loved apricots, so they’re at the table at home, along with roses for grandmother.”

“But you have forgotten someone, mija. There is no gift for your friend.” Her voice held a note of sadness, but I also felt the chide for what it was. She waved her black-gloved hand to one of the empty chairs in the deserted living room and John was there, waving. He looked as he’d always looked and although it was a little startling to see him there, I waved back. Maybe I was asleep, having a dream like my sister.

“And what about this one?” The Lady waved her hand again, and I saw my grandmother as I had never seen her before, strong and upright in the seat next to John. She was knitting a shawl and beamed at me, making me beam back.

“I’m sorry, I …”

“No apologies, the night is short. You will go into the garden and bring back lots of flowers for your grandmother and me, and a ball for John. It is the right thing to do. I will watch your sister and hold your book. Go now, this is important,” she said.

As I snuck past the adults, who probably thought I was going to the toilet, I thought of my school principal and realised the Lady had the same strong, soft voice that you dared not challenge. Some people do not have to scream to impose their will, because a mere whisper has behind it the force of pure steel. I dared not disagree.

Sneaking past the dining room where my father and aunty held court as mum resentfully watched, I entered the hallway and stopped. Tia was too modern to cover her fancy, gold trimmed mirror and I was suddenly terrified to walk past it. I had to, to get to the yard, but I didn’t want to see what was there. I got as close as I could, then pushed myself against the wall opposite, closing my eyes and pressing my face to Tia’s fancy wallpaper, barely daring to breathe. I felt eyes watching me from the cold mirror world and I knew there was more than one figure pressed up against the glass. Something told me there was a man with bloodied hands watching me. There was a woman in white, maybe a nurse, with guilt on her face, because she gave someone medicine that killed them by accident. And there was another figure, younger than the others, who held a bundle, like the shape of a baby, but the child was dead. They were watching me from the world of reflections on this, the Day of the Dead, but I would not turn to face them.

I made it outside and my eyes were grateful for the darkness. In the distance was the outline of our car, because the driveway was for their cars, particularly Tia’s Lexus. It was the height of elegance to us, even the name, Lexus, was beautiful. We had never been inside it. Next to it was a Landrover, belonging to Ronald, Tia’s Australian Butcher Husband. She was so fancy, she had married outside of the genetic pool of lost Latino people that my family constantly hung around. We didn’t fit with the white people, so we found other lost ones and made them our friends. Tia was better than us, because she had married a native, with his own business and a boat. But I had a mission and began to search for flowers.

I didn’t know where to start so I left the front garden and retreated to the back, past the metal gate and big tree that separated the fancy front of the house from the more mundane yard. I didn’t expect my cousins to be playing on their swing set at night, or that my brother would be perched on the top of their slide, watching them swinging like a demented pendulum that rocked the metal frame, standing up, while the other pushed. Their playground was an out of place relic of when they were younger, but at night it became menacing, especially as the boys were too old and big for it, swinging hard. There was something about their laughter that scared me. “Hey, its Rosa, you want a go on the swing?” called Caleb, pushing Taylor as hard as he could. “No thank you,” I said politely.

They scared me, they always had. Something about being half-Australian, with Australian names gave them an armour I would never be allowed to wear. They were born here, not over there and they were older and richer, things that made them BETTER, like an invisible tattoo of success. “Come on, it will be fun,” said Taylor, leaping off the swing with confidence. His sneakers, Nike of course, had made the seat of the swing dirty and now they offered it to me, smiling their shark-smiles. “No no, I’m ok thank you,” I said, and tried to go around them.

Then Caleb grabbed me and sat me on the swing, hard. Barely fourteen, but twice my size, and a million times my confidence, I’m pretty sure he could have killed me and received only praise for being so strong and efficient. They were bullies to us, the two of them, only accepting my brother because he could be moulded into a mini-them, and of course mum and dad didn’t believe me. We were cousins, just playing. It was all part of the game. I held the chains on the side of the swing for dear life.

It could have looked innocent because I didn’t scream, I was too scared. It just looked like two cousins, pushing a girl on a swing. But it was so hard, so fast that as I went feet-first, flying into the darkness, my bladder betrayed me, and I started to cry. Taylor noticed the pee and pulled the swing to a stop, pushing me out of it. “Ew, she’s peed on it, you fucking baby, get inside and clean your arse.”

“Yeah, your arse, your arse stinks,” parroted Caleb. From atop the slide, my brother watched. He was only seven, but old enough to not break the unspoken boy-code. I ran to the second bathroom, blazing past the mirror with my cheeks burning with embarrassment and fear. It took me a long time to dry myself and the familiar urine smell wouldn’t leave without a wash, but at least I looked presentable. I snuck past again, determined.

Back in the safety of the front yard, I delicately pinched every wayward dandelion I could find and then moved on to the thin, weedy daisies, but it was not enough. Tia, like my mother, had geraniums in every colour she could find, so I took one of each, binding them into a small posy. It looked colourful and less pathetic now, so I began to search for the ball. I felt very infantile and a little silly, but I eventually found one on the veranda and I sighed with relief that the Lady would be happy. Composing myself, because my dad hated to see frowning faces at a party, I crept past the laughing parents and went back to the couch.

My sister was still there, but the Lady was not. My book lay undisturbed where I had left it, but there was no sign of her, or the others. But I was used to following orders, so I walked over to the perfunctory offering table Tia had for HER family, where a mango and a cockatoo feather sat in honour of some Australian ghost and added my posy and tennis ball. I stared at them for a sad moment then turned back to face my chair and she had returned.

“Que bonito! Come sit down mija,” she said, her voice still smiling in tone and muffled. The smell of candle wax and flowers was stronger now, as if she’d been walking and her skirt had brushed past them. I sat silently, respectfully as I could. I wanted to apologise for taking so long and smelling like urine, but that didn’t seem right. I don’t think that’s what she wanted to hear. So, I said nothing, I just gazed at her politely and murmured without thinking, “You’re so beautiful.”

Embarrassed, I looked down, and heard her sigh. “Thank you mija. I like to look nice when I visit, so I can remind everyone that they will all meet me eventually. Like her, and your friend,” she said, gesturing at my re-appeared grandmother and John. “But you are sad, mija, porque? Tell me.” Again, the silent insistence of her tone blossomed into a burning need to tell her every worry I had. Would we be poor and unfortunate forever? Why could I see her and no one else seemed to? Did dying hurt? Did my grandmother suffer? Did John suffer as he fell? Am I going to suffer too? Every question that my tiny mind held, all at once was buzzing like hornets trapped in my head to get out. I gasped, overwhelmed, the words not coming.

Sensing something, her black gloved hand pressed her handkerchief into my hand and I felt the burning reality of something greater than me, than Life itself. The hand of the Lady of Death was bones under her lovely glove, that much was clear. I could feel bone, hard and unyielding without skin, holding me with power from beyond.

“The Shadowman, the one who stands at the base of your bed, the one who your sister cannot see? You must wave this at him next time he appears, and he will not bother you again. He is lost and too stubborn to come to me so he bothers the living. You sleep in the room where his wife died. Just wave the handkerchief and do not forget to put out the offrenda for your loved ones, yes? Remember they aren’t gone, you know they aren’t, as long as you remember them.” She leaned forward, eyes peering hard from behind the white mask, and I wondered what held her eyes in place if there was no skin, no muscle. One bony finger poked the spot over my heart and said, “They live in here.”

And when I looked up, she was gone.

NOW

Tonight, my Australian husband and I are going to the neighbourhood Halloween party, which falls on the same day as Day of the Dead. I married a native too, so now I really belong, and while he is dressed as Chewbacca, I am wearing the same outfit as the Lady. We will leave the house without checking our reflections, because the mirrors are respectfully covered, and the offerings are all in place. Among the costumed people, I will see my grandmother and John, and who knows who else, living, or dead. And just in case I run into the Lady again, I have her flowers ready.